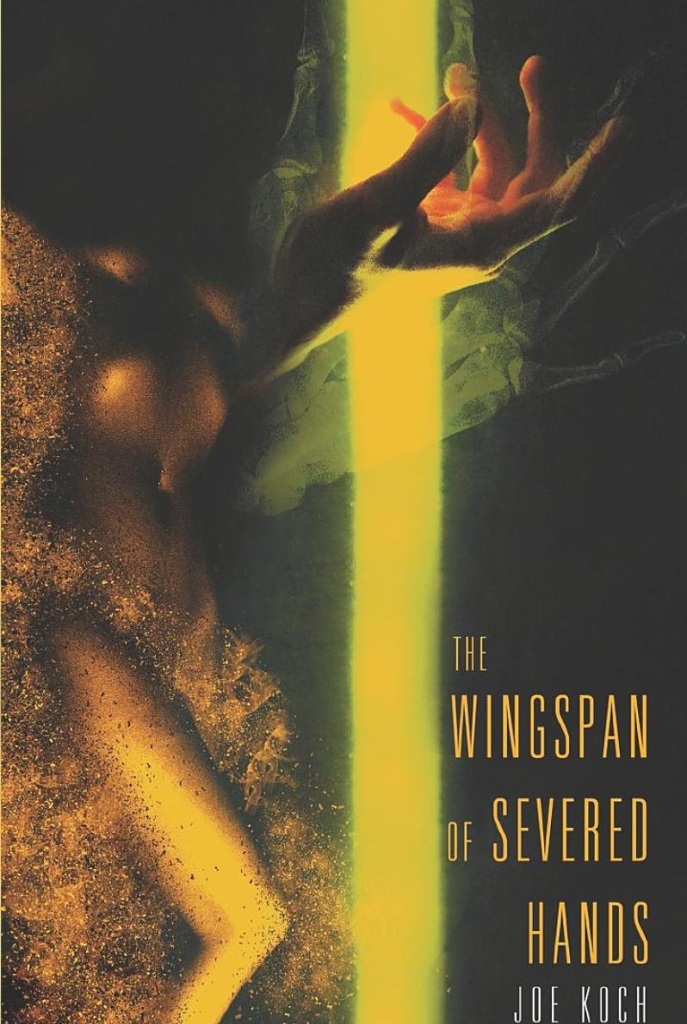

I’ve been wanting to get my hands on this one for ages. The Wingspan of Severed Hands is a 2020 novella written by Joe Koch and I was aware of it since before its release but after its initial publication I struggled to find a print copy for purchase in Canada. Weirdpunk Books recently issued a second print run of the book and this seems to have broken the digital-only barrier I was facing as I was able to finally buy a copy and I’m very glad I did because The Wingspan of Severed Hands is one of the most fascinating works of weird fiction I’ve ever read, a perfect example of avant-garde literature that challenges its reader both with the complexity of its imagery and the artfulness of its themes.

This book is a weird fiction story which gestures directly toward the work of Ambrose Bierce and Robert W. Chambers but it is also a startling interrogation of the question of what it means to be sane and of the ancient Taoist question of whether one can differentiate between objects.

We might start by interrogating a genealogy, or perhaps an archaeology, of Carcosa. This storied city appears first in Bierce’s An Inhabitant of Carcosa in which it is an ancient and ghostly ruin. I say ghostly rather specifically because Bierce’s story is an interrogation of death and the persistence of the spirit, chronicling the revelation that an ailing man is, in fact, a ghost, long dead, who has approached his own grave and in doing so come to the revelation of his spectral nature. Bierce’s story opens with a quote, accredited to “Hali” (likely derived from one of two Arabic alchemists) which proposes different permutations of death as a phenomenon:

“For there be divers sorts of death—some wherein the body remaineth; and in some it vanisheth quite away with the spirit. This commonly occurreth only in solitude (such is God’s will) and, none seeing the end, we say the man is lost, or gone on a long journey—which indeed he hath; but sometimes it hath happened in sight of many, as abundant testimony showeth. In one kind of death the spirit also dieth, and this it hath been known to do while yet the body was in vigor for many years. Sometimes, as is veritably attested, it dieth with the body, but after a season is raised up again in that place where the body did decay.”

Ambrose Bierce – An Inhabitant of Carcosa – 1886

The affective character of this silent and ruined city under the red disc of a darkening sun, ripe with the psychopompic significance of the owl and the lynx was then appropriated by Chambers for The King in Yellow and it’s from Chambers that much of the shared weird-fiction motifs that surround Carcosa – the idea of it as an alien landscape as opposed to (or in addition to) it being a spirit realm, the King in Yellow as the monarch of the ruined city, the eponymous play about the king which brings madness, and the Yellow Sign – derive. In the story The Yellow Sign the model Tessie says, of the awful man who upsets the narrator, “‘he reminds me of a dream,—an awful dream I once had. Or,’ she mused, looking down at her shapely shoes, ‘was it a dream after all?'”

This short story treats these semiotic markers of Carcosa – the play, the sign – as occupying a liminal space between life and death. The agent of the King in Yellow who comes to recover the amulet marked by the Yellow Sign is a cemetery watchman long-dead, the same man who haunted the dreams of Tessie and the narrator. And as such it’s via Cambers that we begin to see Carcosa as a place of questioning boundaries – the boundary between waking and dream, the boundary between life and death.

In the second chapter of the Zhuangzi is one of the philosopher’s most famous fragments:

The Outline said to the Shadow, “First you are on the move then you are standing still; you sit down and then you stand up. Why can’t you make up your mind?”

The Book of Zhuangzi – Translated by Martin Palmer (with minor alterations) – 1996 (original text ~300 BCE)

Shadow replied, “Do I have to look to something else to be what I am? Does this something else itself not have to rely on yet anther something? Do I have to depend upon the scales of the snake or the wings of a cicada? How can I tell how things are? How can I tell how things are not?

Once upon a time, I, Zhuangzi, dreamed that I was a butterfly, flitting around and enjoying myself. I had no iea I was Zhuangzi. Then suddenly I woke up and was Zhuangzi again. But I could not tell, had I been Zhuangzi dreaming I was a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming I was Zhuangzi? However, there must be some sort of difference between Zhuangzi and a butterfly! We call this the transformation of things.

The simplest interpretation of this is to treat it as a question of boundaries and this is so, to a certain extent. It’s true that Zhuangzi calls into question the division between waking and dreaming. But more to the point Zhuangzi calls into question the existence of discrete objects. The Shadow treats itself as an object and points out that its constant fluctuations, first standing still, then sitting down, then standing up should not be tied to a single cause because all causes are interdependent. This prefaces Zhuangzi’s argument that to dream of being otherwise is to be transformed. Instead of discrete objects we see a universe of motion wherein forms are contingent and disruptive change ever-present.

This provides with a basis for grappling with Koch’s challenging text.

The Wingspan of Severed Hands focuses on, perhaps, three interconnected beings. The first is Adira – a daughter of a harsh and controlling mother, someone raised with too much religion and not enough money. The second is Director Bennet – a scientist leading an initiative to rescue civilization from an epidemic of madness brought about by the semiotic contagion of the Yellow Sign. The third is the Weapon – possibly an angel, possibly a butterfly and possibly a god – the weapon is Bennet’s vehicle of global deliverance and Adira’s vehicle of personal deliverance.

The stories of Adira and Bennett begin seeming like disconnected views of the same global phenomenon. Bennet shelters in her bunker building plans to rescue the world from the cultic calamity that Adira lives within. Her mother raises her with the judgmental furor of an evangelical Christian but as the story progresses it becomes clear that her’s mothers theological convictions are not so simple.

Looming over this is the Queen in Yellow – a dead or dying mother god, the monarch of Carcosa, our liminal city where dream and lucidity, death and life, madness and sanity collide in a shattering of dialectical poles.

However as the story progresses the boundaries between these characters become indistinct. We discover that Director Bennet is properly named Adira Bennet and many aspects of her personal history align with those of Adira’s present. Adira suffers a series of shocking mortifications and transformations that harken back to Bierce’s claim that sometimes the spirit, “dieth with the body, but after a season is raised up again in that place where the body did decay”

This progression, and the dual nature of the Weapon as Bennet’s project and Adira’s guardian angel, come about to a climax which is effectively a textual approach to semiotic collapse as the groundings of formal unities are cut out from under the audience one after another. The entire book occupies “the last waking moment between the blackness of sleep and the lucidity of dreaming,” while also taking place as a giant butterfly built of steel and flesh dreams the death of a mad goddess and while also chronicling an abused woman escaping from an ailing but domineering mother for whom she will never be good enough.

It’s not the right question to ask if Adira and Bennet are the same person. Nor is it right to ask whether Adira and Bennet are acting at the same time. It’s even more futile to ask whether Adira is cut to pieces by a mad cult in a disused school pool building only to be resurrected in the bowels of a cosmic hound. This book defies an easy division between the action of the text and the metaphor by which the action is described. These semiotic structures of fiction collapse under the power of Koch’s vision.

I think one of the delightful challenges of this book is the way that it obliterates the idea of narrative fiction as existing within time. If everything is in a constant state of flux and change then time itself must be seen as contingent. Certainly this metastable conception of material law is a thread in philosophy that runs from Zhuangzi to Meillassoux, intrinsically tied to various iterations of dialetheism and I think this provides a lens for looking at the truth of this book. The Wingspan of Severed Hands contradicts itself constantly while simultaneously reifying its own unity. Adira is the history of Bennet. Adira is the ally of Bennet. She is one person, she is not the same person. Carcosa has always been a liminal space and in this book it exists at the boundary between being and the void. It both is and is not; there is a chronological thread: The weapon is made. The weapon gestates. The weapon is unleashed and flies to Carcosa. But simultaneously the weapon appears on Adira’s wedding day, born of her severed hands. It’s made of flesh and metal and language. The weapon is not a tulpa, it is no mere thought-form but it is a thought-form and an angel and a machine. This (non)contradiction is what makes this brief text such a challenging read and I do want to note that this is not an easy book to read. I found myself rereading passages in this as often as I do when picking my way through complicated metaphysical monographs to make sure I understood what I was reading on a scene to scene level. And yet this difficulty is not from any sort of sloppiness. Koch is a powerfully controlled writer with an exceptional grasp of language both as a tool for communicating metaphor and as a sound-based artform: “Shamed by the mirror, by her mother’s hand, hot and damp with uncontrollable, anxious sweat, in the dress so tight it doubled every flaw, flowers in her hair, flowers in her eyes, no time to cry. the teal church carpet reddened Adira’s slapped cheek. She was a ruddy sow marched to slaughter.”

Furthermore Koch has mastered a skill I wish more genre authors would – using all of the senses within his work. The sensory data of this book is like a stack overflow. It’s so abundant that the mind struggles to contain the (non)contradictory sights, sounds, smells, tastes and feelings of the world. Koch tells us to take it all in but what it all is, is madness. And yet for all of this jumble of metaphor and reality, for all that this book is a work of asynchronous subversion of time and identity, it remains a taught thriller about trying to save the world from madness.

But can the world be rescued from madness or only be driven further into it? Is the Yellow Sign a sigil from beyond the stars or the random adornment on the side of an empty journal? It is both. It is neither. And so we have a world that is (not)saved. We have a protagonist who is (not)unified in her own identity.

The Wingspan of Severed Hands is a masterwork of literature. It is as insufficient to call this book weird fiction as it would be to call An Inhabitant of Carcosa weird fiction. It is certainly weird in the Fisherian sense of an overabundance of presence but this is an insufficient description of it. It is such a singular text that the only way to describe it would be to repeat the entirety of it verbatim and so, in the end, I can only say that the only way to grasp this book, let alone to understand it, is to read it. I would encourage people to do so.

Pingback: “Zhuangzi in Carcosa” – a review from Simon McNeil – Horrorsong