So that he should not be one of those who hold their peace but should bear witness in favor of those plague-stricken people; so that some memorial of the injustice and outrage done them might endure; and to state quite simply what we learn in a time of pestilence: that there are more things to admire in men than to despise.

Albert Camus – The Plague

Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End took me a bit outside of my usual comfort zone. Erroneously referred to as “cozy” fantasy, this Japanese fantasy cartoon features an elf member of an heroic adventuring party who is motivated to retrace the steps of her former grand adventure after the death of two of her former party members from old age. Motivated by the death of her old party leader (and possible, but missed, romantic companion) Himmel, she takes on the adopted daughter of of another companion, the priest Heiter, as an apprentice and together the two magi travel north, to the site of the Demon King’s Castle, where Frieren’s party previously saved the world and ushered in a time of peace, so that they can find the place where souls go after death. Along the way they are joined by Stark, a human warrior who was apprenticed to Frieren’s living (but very elderly) companion Eisen. A romance eventually blooms between Fern and Stark. And so the core of the show consists of these three companions traveling northward, getting into little adventures and having remarkably deep conversations.

This show is a pretty classic example of Japanese engagement with existentialist themes. But, where works like Nier: Automata works with Sartrean and Beauvoirian questions of the construction of self-identity, Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End is more indebted to Camus.

This is something we can approach from multiple directions: there is a melancholia to Frieren that, combined with a preoccupation with memory and what it means to revisit a meaningful place after many long years, seems most akin to Return to Tipasa and there is an optimism about humanity that would harken to the Plague. This is a show about memory – the central question early in the series is what it means to be remembered. Himmel and Heiter were very old men when they died and statues of them in their youth dot the countryside. But these idealized statues belie the reality of the men they represent. It’s not that Himmel wasn’t an ideal hero – but he was more than that. He was more than a little bit vain. He was an optimist about humanity. He was a good companion, a good friend to his friends. Heiter was a drunk and a dissolute but also the exact sort of person who would adopt and raise a child as best he could because he knew it was the right thing to do. Our access to Himmel and Heiter comes mostly from the memories of Frieren, a person who has an absurdly long lifespan and who has seen close friends come and go many times in the past. So what does it mean?

We learn that Frieren’s favourite spell is one that was created by her own mentor, now long dead and we know that she loved Himmel in a deep way that is difficult to define but no less profound for its ambiguity. Frieren learns from her companions and adds elements of their passions and interests into her own self-identity. She is always thorough exploring dungeons because Himmel loved dungeons so very much that, in expressing his love, he lives on in her. But the show wants us to understand that memories are fickle. Frieren regularly encounters villages that her party passed before. Nobody lives who remembers their last visit or, in one particularly poignant incident, a single very elderly Dwarf still remains who was there before, but he’s struggling with dementia and, even in life, his memory of that incident dims every day. And so Frieren must watch as the people she knows fades into myth, as even she, herself, becomes a mythological object.

The early episodes of this series are preoccupied with death and loss. When we see how Heiter came to care for Fern she is on the verge of suicide. He persuades her not to because of the loss of memory that her death would entail. Memory is situated throughout this series as a good in and of itself. This scene is one of the first places where we can see the show grappling with the question of absurdity. Fern is a young orphan who watched her parents die and yet it is for the sake of their memories that she steps away from suicide. There is something Sisyphean in persisting to remember when memory necessarily includes the memory of pain. We must imagine Fern happy.

It is good to remain in contact with the past. There is a sadness in the loss of that connection. And the series does start with a remarkably sad tone as we watch our title character openly weep at Himmel’s grave and then again at Heiter’s deathbed. This adds additional poignancy to the episode-long quest to find blue flowers to plant around a statue to Himmel. Frieren seems sincerely joyful as she goes about hunting down Himmel’s favorite flower and it’s a joyous moment, framed by an explosion of petals and a swelling score, when she finally finds the flowers. This scene becomes very nearly surrealist with how it substitutes an abstract symbol for a moment of action.

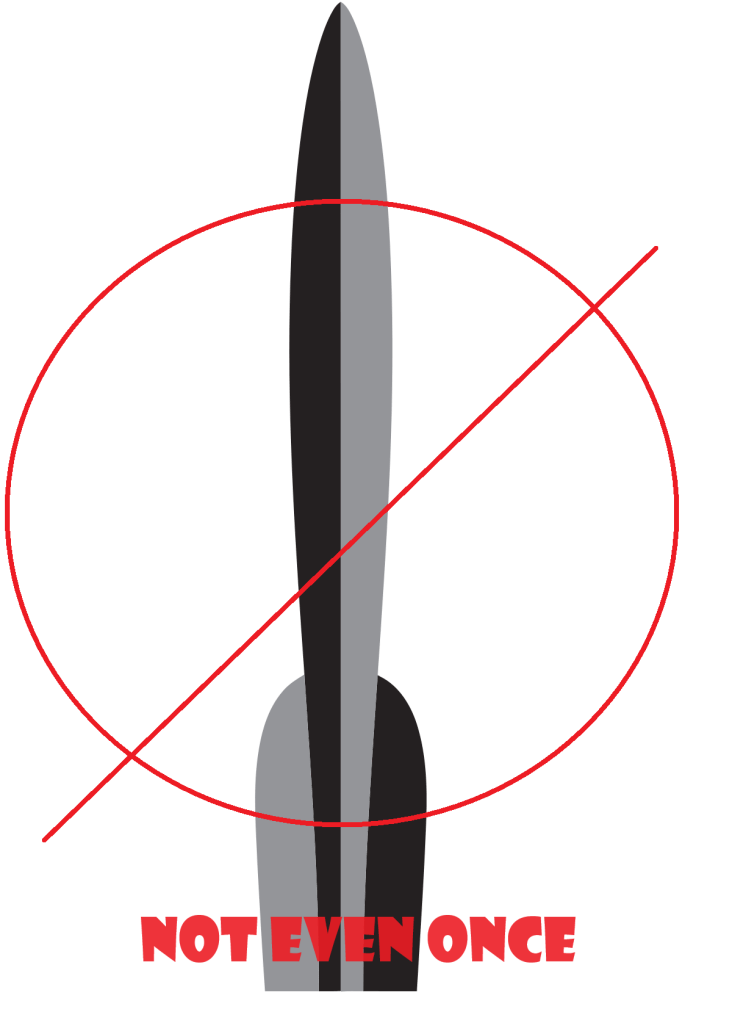

And, of course, the subsequent episode, which brings into the series the idea of magic as something violent and dangerous (something that is only done after establishing how much Frieren uses magic for the beautiful and the mundane) shows us something else about the value of memory. During the Hero Quest the demon Qual was such a terrible threat that they were unable to kill him, instead sealing him away. Qual had developed a specialized attack spell which would penetrate defensive magics. When Frieren releases Qual from his prison she kills him with a single blow after both she and Fern demonstrate how their defensive spells are impregnable against his killing magic.

It transpires that, after trapping Qual Frieren, and other wizards, devoted considerable energy into understanding his spell and into refining defensive magic to respond to it. What was once the state of the art has become the basis upon which the art has been constructed. Qual is remembered as a terrible threat but he no longer is one.

This is an interesting problematization of the show’s initial call to hold onto memory in that it shows how important it is to keep memory in the context of the present situation. This feeds strongly into the dialectic between Frieren and Serie that occupies the final few episodes of the season and demonstrates a remarkable thematic cohesion within the series.

Stepping back it’s interesting to see the reception of Frieren in that it’s often lumped in with “cozy” fiction. I think this is a mistake. The show is paced a bit oddly. It will go two or three episodes at a time full of peaceful, quiet, domestic vingnettes before having an episode or two of horrible violence. This doesn’t follow the “fight an episode” format of many other fantasy cartoons. But it’s not that the discomfiting bloodshed of grimmer or darker fantasy is absent; it’s just spread out. The story gives itself time to breathe and flesh out its cast as fully realized people rather than as heroic archetypes.

And this returns us to the third protagonist of the series: Stark. Our warrior is another generational descendent of the Hero Party. He is the student of Frieren’s dwarf friend Eisen – who has greater longevity than humans but has also got too old for all this adventure business. Stark struggles with fear. He fled his village when it was attacked by demons and is afraid to fight the dragon when he’s first met. Stark also faces a Sisyphean task as his chosen line of work constantly puts him into the position of confronting the things that terrify him the most. And yet he persists.

As they travel across the years of the show Stark and Fern begin a shuddering and rocky romance that is actually given the space in the story to feel real and not just like the obligatory protagonist pairing off that many fantasy stories do.

I think that what really separates Frieren from other series is that it has a sincere interest in people and in the connections they form. One of the key theses of these shows is that what makes people something better than demons is that people: humans, elves and dwarves build community. They show an interest in other people not just as instruments of their will and desires but as other subjects with lives, wills and desires of their own. Even some of the less savory people of the show, such as Übel are differentiated from demons by the extent to which they care about others.

In fact, Übel is particularly important for establishing this distinction. A trouble-maker and a merciless killer, Übel is particularly good at piecing together how other mages magics work. She accomplishes metamagical acts that the show tells us should be impossible, driven entirely by the intensity with which she concentrates her attention on the internality of her targets. Übel sincerely cares about other people, even her victims, in a kind of a perverse way. She understands that the key to people around her is their own internality and, especially when engaged in violence against other people, she strives to build empathy for those around her. This nearly paradoxical relationship divides Übel clearly from demons like Aura the Guillotine. Aura is intelligent, powerful, cunning and charismatic. She is also purely individualistic. And that unwillingness to understand the internality of others is what kills her. Frieren wipes her out with ease because her solipsism makes her easy to dupe.

Humanity is presented as flawed. Aristocrats are haughty and tempermental. Wizards are prone to feats of absurd violence and treat life cheaply. While the series shows considerable affection for the peasantry they, too, are not idealized. Even the peasantry make mistakes. But the show tells us that people working together to form community can overcome the absurdity of their situation not in some climactic battle that sets the world right but in a continual process of building up even as things fall apart again.

The Hero Party ushered in an era of peace and yet Fern’s parents died in war only a few decades later. When Heiter takes her in it’s because he believes it’s what Himmel would have done in her place. The absurdity of the world is overcome again and again.

As the series progresses to its final arc the show becomes even more pointed regarding the absurd. Frieren has a tendency of getting trapped in an undignified position. This is a recurring visual gag going as far back as the first few episodes. We often, in montages, see the back half of Frieren protruding from an object after she allowed her curiosity to override her better judgment.

The classic version of this gag is to show Frieren caught by a mimic. The way mimics present to magical senses is such that there is a 1% chance a chest containing a magical item such as a grimoire will falsely register as a mimic. On this basis Frieren regularly disregards her personal safety to open mimics in the off chance that they’re actually treasure chests with grimoires in them.

And this helps us get at how Frieren’s immortality is really deployed thematically. Early in the series Fern complains about Frieren’s squandering of her considerable talents on mundanity to a herbalist they’re staying with. The herbalist explains that Frieren, being ancient beyond reckoning, has a different perspective on the world and on time. The herbalist describes this as wisdom. This seems dissonant with the sort of person who will take a 99% chance at getting chomped by an angry monster for a 1% chance at treasure. But the point is raised that, over her vast life, Frieren has got many grimoires out of many treasure chests that had a 99% chance of being mimics instead. It’s absurd, of course, in both senses of the word. But the lesson Frieren, as a character, teaches us is to embrace absurdity in all its forms.

And this brings us to the dialectic between Frieren and Serie.

Serie is an even more ancient elf than Frieren. Called the living grimoire, Serie taught Frieren’s mentor and has shaped human magical institutions for the milennia that followed. Serie has literally forgotten more about magic than most beings know – something hammered home by the show’s presentation of how Serie gifts any one spell she knows to any mage who passes the first-class examination. Doing so mystically causes Serie to forget the spell she has taught (though she can devote centuries to relearning these spells, something she doesn’t see as a major problem on account of her agelessness.) Serie doesn’t like Frieren much and actually fails her from the first class mage exam on the basis that Frieren is not the sort of mage that Serie wants her to be.

Serie sees magic as project in the sense of the word deployed by Bataille – that of something imposed from without as an ordering purpose or telos. Serie thinks magic should fuel ambition in some way. She treats this nebulously. It is not that every mage should be a would-be conqueror. But rather it’s that every mage should treat magic as a tool for accomplishing a goal that is something that could be validated as valuable by others.

Frieren runs counter to this. She collects spells as a hobby and has a lot of interest in hedge magic. Fern expresses frustration that Frieren spends so much time chasing spells that do ridiculous and pointless things such as turning sweet grapes sour or making a cup of hot tea. But Frieren says she has been improved by this hobby – that she was more apathetic before she did. Her bumbling around the countryside collecting little, pointless, useless spells helps her to empathize better with others. Frieren celebrates the idea that magic doesn’t have to have a project, that magic is something that goes beyond the bounds of utility or even of beauty (an objective for magic to which she is more closely aligned).

Considering how this show plays with the idea of future generations iterating upon the lives of their predecessors it’s hard not to see Frieren’s difference from Serie as being just such an iteration. But, of course, this iteration is absurd too. Despite the Hero Party ushering in an “era of peace” war didn’t vanish. Many mages remain soldiers or assassins who use magic to kill. Frieren kills demons without remorse and with overwhelming force. In the face of this it seems somewhat absurd to spend decades bumbling across the continent helping farmers and herbalists with mundane tasks in exchange for room, board and a few useless spells. She could be a great person. She was a great person. And, since it’s heavily implied that she’s still pretty young by elf standards she has much potential to continue being a great person. Instead she’s going on a years-long quest to see if there might be a place where the souls of the dead gather, a place she might see Himmel one last time. Serie responds to absurdity with the order of project. Frieren responds to absurdity by openly embracing it and riding within her condition. There’s a sense of wuwei to her actions.

From a critical perspective this puts Frieren, as a character, into the same category of wizard as Le Guin’s Ogion the Silent. Frieren’s magic is the lawless magic that will not serve project, the inarticulate magic that pushes us past the bounds of experience. I know it’s odd to situate a peaceful, quiet, show about small relationships as if it were aiming for the sorts of limit experiences we usually associate with Barker’s fetish demons and yet in her rejection of project in the face of the absurd there’s no other word for it. Frieren’s magic pushes past experience via uselessness rather than via pain but it pushes past experience all the same. If I had a complaint with Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End it’s that it ends rather abruptly. The last arc of the season takes place at a bottleneck city. The protagonists need accompaniment by a first-class mage to continue north. Fern passes while Frieren fails and then they just leave the city again. This is likely an artifact of its adaptation from a manga. It seems an appropriate end to a chapter in the middle of a book. It is a less appropriate end to a season of television.

But in a way this unsatisfying conclusion also serves the goal of asking the audience to wholeheartedly embrace absurdity. There was a situation. Then it ended and everybody moved on.