Yesterday saw the flatulent release of yet another always-already tired culture war publication with the unveiling of Compact upon an unhappy public. The main event of this publication was a Slavoj Žižek movie review for Moonfall and Don’t Look Up which served as a platform from which Žižek could deploy his patented blend of Lacan and Hegel to argue for a dialectical and psychological reading of active conspiracism and passive liberal platitude in the face of catastrophe.

It was very typically Žižek and if you have read literally any other media criticism by the famous philosopher you’ll recognize it all too easily. Frankly the best thing I can say for Žižek’s article is that it was clear he at least watched Moonfall, which makes this review more rigorous than some of his other 2022 content. But we’ve seen this schtick before and it seems increasingly like Žižek is a one-trick pony. This was ultimately far too predictable and, frankly, dull to serve as the basis to a rejoinder to the Compact crowd.

Rather it is a second article in Compact’s initial slate that drives home the sad absurdity of this social-conservativism-with-healthcare style publication. That is the toweringly stupid piece “The Case Against Aesthetic Castration” by Adam Lehrer. If only Žižek had looked for idiocy among his fellow contributors rather than in nature this publication might have been interesting. Instead it becomes yet another piece of culture war panic only dressed up in pseudo-academic language and dancing around in the visual arts.

Lehrer begins this article by stuffing his preferred strawman with Andrea Dworkin’s hottest 1980s takes and then proposing that the 2017 MeToo movement represented a form of castration wherein the libidinal investment of men in the arts was cut off.

What follows is an all-too-predictable format for this particular brand of culture war salvo: a series of broad and laughable generalizations supported with a handful of anecdotes that try to present how reasonable his fear of a woke-too-far position is.

Lehrer brings attention to accusations of impropriety leveled by Julia Fox against Chuck Close, being sure to mention that Close uses a wheelchair in doing so. It’s obvious he’s trying to frame this as a narrative of unfair victimization. He elides that Close was caught up not in one comment to one model but in a pattern of behaviour documented over the course of over 20 years. In doing so he actually misses a potential defense of Close in that, after his death, his neurologist proposed his declining comportment may have been a consequence of frontotemporal dementia. This is because, to the culture warrior, a person is best reduced to a single anecdote. “An injustice happened here, once, and taken alone it invalidates all attempts to change power relations,” they seem to say.

He then goes on to lament the good old days when heterosexual men could sell more paintings of naked women without feeling shame. He provides no evidence that such shame truly exist unless you posit the only way to hire a nude figure model would be to trick a woman into your studio under false pretenses and then, while alone, ask her to disrobe while making sexual comments to her.

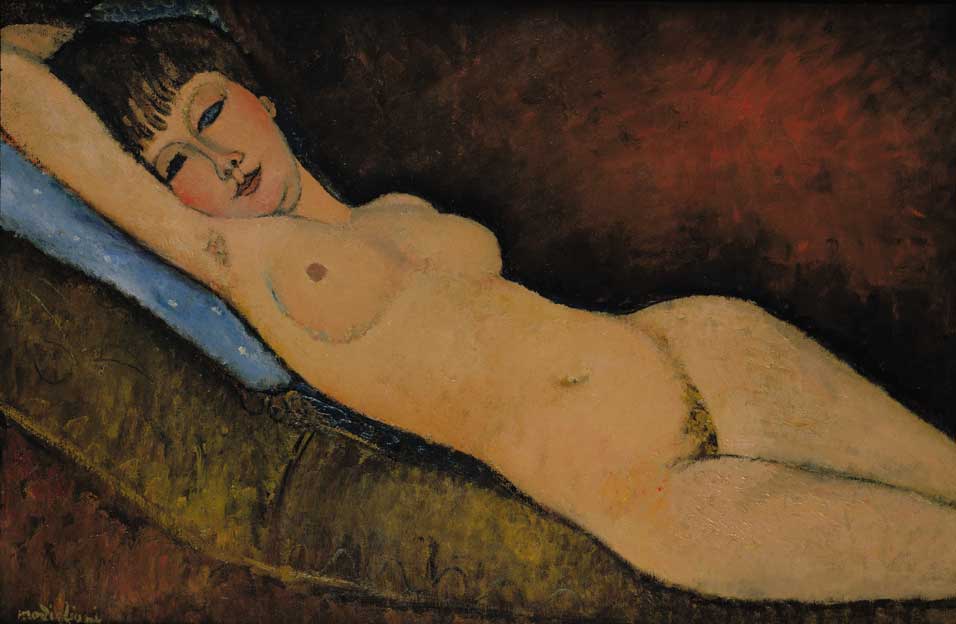

Now far be it from me to demand less sex in art. And while I’m not exactly heterosexual my taste is quite broad and I’m not the sort to declare a sexual male gaze in art to be an intrinsic moral peril. (Women are hot and I’m a man. That I also think non-women are also hot is neither here nor there for my relationship to gaze in art.) Let he who has never advocated for Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers and who has never waxed on about the power and beauty of Matisse and Modigliani’s figure work cast the first stone. I mean while this bilious culture-war missive was being published I was engaged in a public debate over the relative quality of Egon Schiele, an artist who was known specifically for figure-paining of women.

Rather I would deny his premise that men are forbidden from investing their desires in work is a valid premise. I mean, Benedetta came out just this year and last I checked Paul Verhoeven was a man. He certainly isn’t an aesthetic eunuch. But Lehrer complains that the female nude has been banished from art just on the basis of absence of figure painting from a single recent MoMA exhibition.

He then turns to disavowing that counter-examples of men getting along just fine depicting heterosexual desire count, excluding them because this man is too rich to worry about being cancelled, that man is only allowed because his subject is his wife, etc.

What results is a castration of the gaps wherein a problem of men not being allowed to express desire exists but with an increasing series of increasingly ludicrous exceptions. And yet we are made to feel this is some sort of crisis? Ultimately his pronouncement is that, “Male artists must reclaim their manhood,” though he fails to prove any men ever actually lost it. Of course he must make exceptions by excluding homoerotic desire from manhood. By excluding love of a wife from manhood. By cutting and cutting and cutting away at male desire so that all that remains is a fading old painter, wracked with dementia, leering and making naughty comments at a model. I suppose that, if one has such a tiny and impotent view of male desire, the exclusion of that small element might seem like a castration. But the only one cutting at masculinity in these circumstances is Adam Lehrer. If he is afraid of castration so terribly perhaps it’s time he put down the scissors.