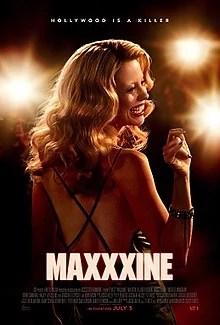

MaXXXine (2024), the capstone installment in Ti West‘s X trilogy, took me somewhat by surprise. Considering the ground tread in the prior films, X and Pearl, I expected, going into the film, something that might tread similar ground to Scream 3. This was very much not the case.

Instead, MaXXXine delivers a thematically messy conclusion to a thematically messy trilogy which largely serves as a vehicle for demonstrating the talent of Mia Goth and for showing off the variety of movies that West, personally likes to watch.

Maxine, having escaped from the clutches of Pearl and Howard at the conclusion of X has built a career for herself in Los Angeles as a porn star. But the hard-working and celebrity obsessed Maxine has her sights set higher than a career in dirty pictures and peep shows, telling horror director Elizabeth Bender, that women in pornography “age like bread, not wine.” Now approaching her mid-thirties Maxine needs an off-ramp and she believes horror cinema is her ticket.

Bender sees an intensity in Maxine’s audition that she believes belies talent and casts her, over the objection of the studio which is already facing protests for the film – “The Puritan 2” – a sequel to a previous breakout satanic possession movie which transports the action to the 1950s. Bender, for her part, wants to strip the veneer from the 50s and demonstrate the rot at the core of America’s mythologized decade of innocence.

Two complications interfere with Maxine’s plans for an ascent to stardom: the first is the unwanted attention of a slimy private detective John Labat, played with an amusing level of scenery chewing by Kevin Bacon, who has discovered her involvement in the murders in Texas years previous. The second is the omnipresent shadow of real-life serial killer Richard Ramirez, the Night Stalker. When Maxine’s friends and colleagues begin turning up dead, brutalized and branded with the mark of the pentagram, police investigating the Night Stalker believe they have a copycat on their hands – and believe Maxine has information that can lead them to this killer.

With as much drawn from the oeuvre of James Ellroy and Raymond Chandler and from the style of Mario Bava as from more conventional iterations of the slasher, Ti West continues trying to demonstrate his artistic chops throughout the film. “I’m an artist,” Elizabeth Bender says. “This isn’t just a video nasty,” she says of film-within-the-film The Puritan 2. She insists she has a message to communicate. But, despite turning out an entertaining story with some beautiful aesthetics Ti West struggles to communicate a coherent message. He hints again at the idea of doubling in this story as the copycat killer is doubled against the Night Stalker, but ultimately struggles to resolve the original doubling from X. We’re left wondering what exactly is being communicated with how the story compares Maxine to Pearl.

Pearl is a yawning absence at the center of this film because, of course, Pearl never got to Hollywood. But Maxine starts off in Hollywood and, despite John Labat’s bluster and the unwanted attention of both police and a serial killer the one thing that never really seems threatened throughout the movie is her notoriety. Maxine’s fame is assured. The only question that seems unanswered until the resolution is whether she’ll be a famous star or a famous victim.

The film opens with the Bette Davis quote, “In this business, until you’re known as a monster you’re not a star,” and Elizabeth Bender almost explicitly incites Maxine to vigilante violence, first comparing her horror protagonist to Dirty Harry or Paul Kersey and then telling Maxine to take a weekend to resolve whatever personal issues might be interfering with the production schedule. But, despite a capacity for violence, Maxine’s antagonists are so openly monstrous that it’s hard to see her actions as rising above the level of many protagonists of the slasher and rape-revenge genres. By the time she dispatches Labat he’s already blackmailed her, followed her with a camera at the behest of an employer we know to be the killer and chased her about the Bates Motel set with a revolver, explicitly threatening her life. He’s pursued her into the bathroom of a dance club and claimed to be a criminal while, again, waving a gun. Other targets of Maxine’s violence include a Buster Keaton impersonator who follows her down an alley with a switchblade and, of course, the killer and his cultists. Frankly there’s only two moments in the film where her actions rise above the most unambiguous examples of explicit self-defense. With this in mind Maxine’s actions don’t feel like a person giving into monstrosity in order to achieve stardom. They feel like a woman pushed to the edge by a host of monsters assailing her from all sides.

I do think a psychoanalytic read of MaXXXine is stronger and here is where comparisons to gialli become relevant. Frankly Ti West begs the comparisons by dressing his killer, until the final act, in a near carbon-copy of the costume of the killer in Blood and Black Lace. But for all that the film uses POV shots from the black-gloved killer and red filters over the set lamps to invoke the aesthetic of the giallo it misses the significance of the mystery aspect.

I think there was an attempt to make this movie into a mystery or detective film of a sort. The killer is, through the first two acts, a mute pair of hands or a shadow in a corner. His rage at seeing Maxine in a peep show is palpable but the reason remains opaque in the moment. But this is a problem because there really isn’t any mystery in this film. The victims, excepting one, all tell Maxine where they’re going before they disappear and Labat literally hand-delivers Maxine an invitation. The identity of the killer is telegraphed in the literal first frame of the movie and the eventual reveal carries entirely no shock as a result. With the killer kept silent for so much of the movie there are many missed opportunities to establish what Maxine is actually fighting against, what ideology she opposes to juxtapose against the mentorship off Elizabeth Bender. But, perhaps, it’s sufficient to signal that, as many woman-fronted Giallo films were deliberately seeking psycho-sexual reads, that we should interpret this film such too. Maybe that’s all West wanted to signal to the audience with these indicators.

But this returns us to the problem of how we are supposed to parse the doubling of Maxine and Pearl. Certainly Pearl is a psychosexual thriller far more than a conventional slasher. Mia Goth’s portrayal of the dust-bowl era farm girl striving for fame and sexual self-determination and instead finding violence and death was deeply internal in its focus and her moment of pained realization at the end that she had trapped herself in a life of domesticity with Howard was one of the best final frames in horror cinema. But sex, for Maxine, is just work. When the casting directors ask her to show her breasts she does so with business-like neutrality. Her work in porn is coming to a conclusion not because of any issues with sex so much as a concern that she has a limited duration career in a business that prioritizes youth. She desperately wants to be famous. But, again, her fame, as such, is never in peril, only the tenor of it.

Mia Goth does an excellent job. Maxine feels like a fully realized character both in her quiet moments watching movies with her video-store-clerk best friend Leon, in her coke-fueled moments of frenzied work and in her carefully plotted trap for Labat. Her moments of vulnerability at Bates Motel and during the head cast scene communicate the depths of the character well. But Mia Goth is a very talented performer and her doing a good job bringing full life to a character is kind of what I would just expect from her. The film wants to tell us that the unresolved core conflict in Maxine’s psyche is oedipal. She was set up to desire fame by her father, a televangelist cum cult-leader, who saw her as the future leadership of the church until she set him aside. This would tend to suggest a straightforward Freudian read that, by blasting her cult-leading, serial-murdering, moral-majority doomsday preacher of a father’s head off with a shotgun, she has resolved her Oedipus complex and is able to resolve herself as an individual. Except, of course, Pearl, our failed would-be star, also killed her father and still ended up trapped in a life of obscurity.

Maxine seems to accredit her success to hard work, and certainly she does work hard. In fact it often seems like her rampant cocaine usage is principally so that she can power through three jobs at once while also being stalked by a killer and his pet detective. But it doesn’t really seem like the other victims across this trilogy lacked her effort or her ambition. Lorraine, in X, had plenty of ambition and seemed perfectly willing to work hard. Maxine survived and she did not mostly due to dumb luck.

The series occasionally dallies with the idea that stardom depends on a nebulous and impossible to define x-factor but never commits to the theme sufficiently to drive this message home.

The film, and in fact the whole series, is also quite ambivalent on the moral character of art and exploitation. It’s honestly kind of odd to see a movie so intimately possessed with the idea of gaze that doesn’t really have anything at all coherent to say about it.

The movie is critical of religion, certainly, this has been consistent throughout the trilogy, which always codes its antagonists as hardcore Christians. But, despite a deathbed conversion, Labat is an avowed atheist while Maxine seems unwilling to say much about religion one way or the other. The third-act revelation that the supposedly satanic killings were being conducted by a Christian sect that wanted to rescue its collective daughters from the satanic influence of Hollywood was well foreshadowed by scenes of Christian morality protesters at the studio gates and a grumbling speech from Bender about studio fears around censorship and the opinions of moral crusaders. But leaving the killer so completely off-screen for the first two acts as this film did undercuts this message. We never really hear from him at all until he’s in his “revealing my whole plan” monologue period. This is somewhere where West could have taken a lesson from Wes Craven whose killers never shut up and, as a result, are able to elucidate what motivates them thematically before they reveal the mechanics of their plot.

All in all what we get with this trilogy of films, and with its final installment in specific, is a thematic mess that fails to commit to a theme. Instead we get three or four half-baked themes. However I still really liked the movie. It’s very funny. There were several laugh-out-loud moments across the film and none of the obvious jokes failed to land. Giancarlo Esposito (who plays Maxine’s agent) and Kevin Bacon both steal their respective scenes largely on the strength of their comedic timing. It’s also a beautiful film, with strong cinematography, makeup and lighting throughout. The script works well on a scene-to-scene level and the characterization is consistently strong. I enjoyed spending time with these characters. The kills were somewhat perfunctory but this movie is not exactly a slasher film so I can live with that. And the practical effects were well done throughout.

I think MaXXXine is, ultimately, a perfectly appropriate capstone for the X trilogy. It is a showcase for the talent of very well cast actors who are clearly bringing their a-games and it is a clearinghouse for the various cinematic influences Ti West seems to love. The sense of people doing a thing they like doing with technical virtuosity pervades both this movie and the trilogy as a whole. If West can learn to commit to a theme and explore it with a bit more care in the future he can probably become a great director. Until then he’s doing particularly well-performed mashups of horror’s greatest hits. But it is, at least, a very entertaining ride.