Whom Thunder hath made greater? Here at least We shall be free; th’ Almighty hath not built Here for his envy, will not drive us hence: Here we may reign secure, and in my choyce To reign is worth ambition though in Hell: Better to reign in Hell, then serve in Heav’n. --- John Milton, Paradise Lost, Book I Those who restrain desire, do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained; and the restrainer or reason usurps its place and governs the unwilling. And being restrained, it by degrees becomes passive, till it is only the shadow of desire. The history of this is written in Paradise Lost, and the Governor or Reason is called Messiah. And the original Archangel or possessor of the command of the heavenly host is called the Devil, or Satan, and his children are called Sin and Death. But in the book of Job, Milton’s Messiah is called Satan. For this history has been adopted by both parties. It indeed appeared to Reason as if desire was cast out, but the Devil’s account is, that the Messiah fell, and formed a heaven of what he stole from the abyss. --- William Blake, the Marriage of Heaven and Hell - The Voice of the Devil I'm not fazed, only here to sin If Eve ain't in your garden, you know that you can Call me when you want, call me when you need Call me in the morning, I'll be on the way --- Lil Nas X - MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name)

Permit me a moment of algorithm chasing because apparently the Satanic Panic is back! This time, the terrible satanist who is corrupting the morals of the youth and turning people away from the frigid restraint of the Christian God is the American musician Lil Nas X.

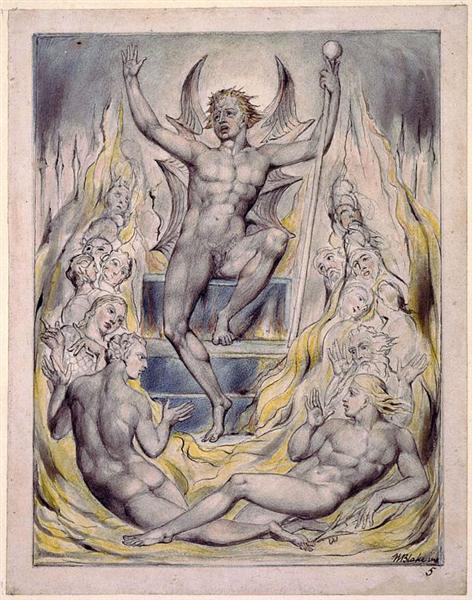

See Lil Nas X has been playing around with Milton in his latest video:

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

This video is roughly divided into three principal scenes. In the first he is Eve in the garden and is seduced by the serpent. He is also the serpent, seducing.

A transition shows us some Greek text burned into the tree of life. Greek is not one of the languages I can read but with some digging it appears to be a quotation from Aristophanes’ description of the division of the ideal forms in Symposium, AKA the best thing Plato ever wrote:

For the rest, he smoothed away most of the puckers and figured out the breast with some such instrument as shoemakers use in smoothing the wrinkles of leather on the last; though he left there a few which we have just about the belly and navel, to remind us of our early fall. Now when our first form had been cut in two, each half in longing for its fellow would come to it again; and then would they fling their arms about each other and in mutual embraces

Next he is a rebel being led in chains to the center of a marble auditorium. He is also the guards guiding him and the spectators watching. The gender coding in the visuals is simultaneously explicit and scrambled. The guards wear denim and their clothes and hair are blue, but they also wear large rococo (womens’) wigs and ostentatious (womens’) jewelry. The pink-coloured rebel has a more masculine hairstyle and wears a (masculine) loincloth and a fur sash over one shoulder. He makes his plea, but the judges of the auditorium are either critical reflections of himself or they are rigid and leering statues.

In the Marriage of Heaven and Hell, William Blake engaged in an extended critique of the theologian Emanuel Swedenborg. Swedenborg was a theologian and a natural philosopher whose work centered around the concept that the account of Genesis was a description of the moral and spiritual evolution of man away from the material and toward a form of purely spiritual being. Swedenborg was deeply Manichean in his view, rigidly dividing spiritual good from material evil. However Blake saw in Swedenborg a form of frozen fixity that would lock humanity as rigid as statues, saying:

Without contraries is no progression. Attraction and repulsion, reason and energy, love and hate, are necessary to human existence. From these contraries spring what the religious call Good and Evil. Good is the passive that obeys reason; Evil is the active springing from Energy. Good is heaven. Evil is hell.

Blake believed that this unification of these dual opposites was necessary to advance humanity in knowledge and grace. (Being something of a gnostic meant that knowledge and grace were largely the same thing to Blake.) However we can see this reflection of unity of opposites both looking back in the direction of Aristophanes in Symposium and forward to Lil Nas X’s interpretation of Milton. Because let’s not put too fine a point on it – in this scene the Rebel is Lucifer, and these rigid frozen statues, mere reflections of his own glory, are the angels loyal to a God who appears only as a bejeweled statue in the background. However just like the captors and the Rebel God is yet another reflection of Lil Nas X.

The statues pelt the Rebel with stones and he Falls but at first his fall seems an ascent. He drifts toward a heavenly light. An angel in silhouette appears above him and seems to be beckoning him toward the light. Then a stripper pole descends from the sky and the Rebel grips it willingly and dives head first into Pandaemonium. And in hell we finally find an actual Other in the form of Satan. Our Rebel walks confidently to the throne of the Devil and gives him a lap dance. But the seduction is a trap; at the conclusion of the song, Lil Nas X snaps the devil’s neck and assumes his crown, growing black wings as his eyes glow with heavenly light. Better to reign in Hell, then serve in Heav’n, right?

So we have in this video a clear engagement with two principal texts: Milton, from whom the majority of the imagery engaged by the video descends and Symposium in which the idea of a division of the ideal (multi-genedered) form into incomplete male and female halves is served as the context of a form of Fall from a state of grace.

Blake had two principal missions in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. The first was to continuously dunk on Swedenborg. But the second was to propose that the fall from grace could only be overcome by a return to unity – that a rejection of the base, the energetic and the terrible would stall any hope of progression and leave people nothing but apes groping after Aristotle among the refuse of their own cannibalistically cleaned bones. Blake exhorted people to overcome their internal divisions and saw that unity in Milton, proclaiming, “Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is because he was a true poet, and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.” Of course, Blake was well aware that Milton saw Satan as the antagonist of Paradise lost. He rejected that authorial intention in favour of fusing the expressed purpose of exhorting God’s glory with the loving render of the Fall of Lucifer. As such, the video for Call Me By Your Name becomes a recursive return of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

Recursion and Return

In Difference and Repetition, Deleuze talks about Plato’s conception of difference, saying:

In his case, however, a moral motivation in all its purity is avowed: the will to eliminate simulacra or phantasms has no motivation apart from the moral. What is condemned in the figure of simulacra is the state of free, oceanic differences, of nomadic distributions and crowned anarchy, along with all that malice which challenges both the notion of the model and that of the copy. Later, the world of representation will more or less forget its moral origin and presuppositions. These will nevertheless continue to act in the distinction between the originary and the derived, the original and the sequel, the ground and the grounded, which animates the hierarchies of a representative theology by extending the complementarity between model and copy.

It behooves us to look at the relationship between MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name) and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell as being something like an original and a sequel as this deployment of Platonic unity to challenge a dualistic and Aristotelian theology, combined with such a clear and textual response to Milton unites the two. However this situates these two works in a moral relationship that we should look askance at. Although we can look at the former as the ground upon which the latter arises, we should not assign a moral direction to it – neither Plato’s favoring of the ideal or original nor Blake’s revolutionary futurism should be used to assign a moral weight to Lil Nas X. This is in part because the repetitive aspect of this work cannot be pried loose from the differences that suffuse it.

The narrative frame of Blake’s poem is something akin to Dante touring hell and heaven. In his case, his guide to the afterlife is an angel representative of the frozen theologies he believes to be dead ends. Blake problematizes this narrative by taking command of the tour and instead guiding the Swedenborgian angel into a vision of the cosmos that can progress into the future. With Lil Nas X, instead, we get a deeply personal interrogation of queer relationships and distance in the time of COVID-19. However these differences in subject are in turn supportive of the way in which both use Plato to unify a divided being. For Blake the divided being is humanity itself. For Lil Nas X it is the divide he feels within himself – between the presentation he has to show the world and the lived experience that represents the totality of himself. Lil Nas X describes a division against himself which is healed in the assumption of the mantle of satanic sovereignty. Blake describes a division within humanity which is healed in the assumption of a satanic bible. In Difference and Repetition Deleuze discusses Hume’s idea that a repetition is that which creates no change in an object but, through the sequence of returns creates a change in the observation of the subject. After a series of AB AB AB AB A we come to expect that B will follow. This sort of recursive repetition is thus something we can observe in these responses to Milton. When Milton’s satanic protagonist is deployed, can platonic attempts to resolve duality not be expected to follow? In this way, this artistic project continues to be the iterative repetition upon which new art is forever remaking itself on the bones of the old as clearly here as it is when The Hu rearrange Sad But True. And just as these two elements call to each other, we expect that repetition to return a revolutionary frission that overturns orthodoxy. Blake roared into the void of popular theology in hopes of overturning a dead, static, frozen faith. Lil Nas X displays a fluid sense of gender and a deeply queer sexuality that is equally revolutionary within American music – a space that has previously been hostile to men playing with gender this way.

Deleuze says, “In its essence, affirmation is itself difference,” In asking, “is it this thing?” and announcing, “yes it is this thing!” we engender a difference. This repetition of themes asks us to affirm the revolutionary. Just as Sad But True asks us to affirm how every return to the garden of life and death may allow us to make different and meaningful choices, so too does Lil Nas X affirm that there remains revolutionary potential in the image of Satan just as there was in Blake’s day. In fact, while Blake toiled in obscurity, Lil Nas X managed to incite furor of the multitude with a dance and a pair of expensive shoes. A monstrous offspring of Hume and Kant, Deleuze’s philosophy of difference still recognizes that one iteration of a series cannot arise until the past has ended. The process of difference is a violence, a destruction, and one that is necessary. He praises Nietzsche for his cruelty and love of destruction because it is only through those vectors that we can approach a reasonable understanding of difference within recursion.

And this revolutionary understanding is ever-necessary as we continue fighting the same fights. The satanic panic is back! And of course anybody who lived through the homophobia of the 1980s or the bi panic of the 1990s can see the recursion, albeit with difference, in the transphobic panic of today. In such circumstances, a queer man demonstrating the unity of the masculine and feminine within him through the old formula of Blake and Milton is revolutionary. One last time to Deleuze. He says that, “there are two ways to appeal to ‘necessary destructions’: that of the poet, who speaks in the name of a creative power, capable of overturning all orders and representations in order to affirm Difference in the state of permanent revolution which characterizes eternal return; and that of the politician, who is above all concerned to deny that which ‘differs’, so as to conserve or prolong an established historical order, or to establish a historical order which already calls forth in the world the forms of its representation.” In the satanic works of the poets: Milton, Blake and Lil Nas X we have then the first of these forms. And it is, of course, opposed by those who would deny that which differs. There are a multitude of politicians and politically minded people who would prolong the historical order that denies the unity of masculine and feminine that lives within every person. There exists a multitude of politicians and politically minded people who see nothing but menace in the fires of Pandaemonium and the throne of Satan, who see nothing but threat in a pair of black sneakers marked with the pentagram. It is, perhaps, a small revolution to dance on Satan’s lap and steal his crown. But in this little act of revolution, Lil Nas X has announced a change in the sequence of the world and the minds of the subjects who observe him. And for that he deserves to be lauded.