Hope is not an optimistic emotion.

When we discuss optimism we can start by returning to that very early definition of optimism as an emotional position: the glass is half full. Optimism is grounded in an assessment of material conditions. The glass is an object. Its condition – being half-full of water – is a part of its facticity. The water, too, is an object. The optimist begins from the material conditions that exist and extrapolates how the good arises from them. While an optimist has one eye on the future state of the object their gaze is fixed first upon the conditions as they exist.

Hope is far slipperier. In some ways it is an expression of despair. To hope is to observe the abjection of the material and to reject that as the basis for analysis, instead looking toward some outside agency to swoop in and make things better. The optimist, looking at the half-full glass might extrapolate that there is water to be had. The hopeful imagines somebody will bring them more instead.

This feature of optimism – the tendency toward agency – was remarked upon by Antonio Gramsci in his prison letters when he said, “My own state of mind synthesises these two feelings and transcends them: my mind is pessimistic, but my will is optimistic. Whatever the situation, I imagine the worst that could happen in order to summon up all my reserves and will power to overcome every obstacle.” Gramsci’s assessment starts from a material basis and, as one might expect of a Marxist in an Italian prison during the reign of the fascists, he finds his material condition unfortunate. However Gramsci maintains an “optimism of the will” – a revolutionary optimism that demands that the revolution never ended, the workers have not been defeated, so long as one fighter draws breath and continues to fight. Gramsci suffered imprisonment and maltreatment for much of his too-brief life. But his optimism left behind him a legacy of academic work that forwarded revolution for decades to come. What of hope? Hope never lifted him from his prison nor overthrew the Fascist regime in Italy. But the Salò Republic fell and Communist partisans slaughtered Mussolini like the pig he was. This agency is not the object of hope but of such a revolutionary optimism.

However this optimism of the will – this sense that a person can start from their material basis and enact meaningful change – that the words of a neglected prisoner can be one of the sparks that leads to the death of a fascist demagogue – depends on being enmeshed in history. By history here I don’t mean an account of the past but rather a continuous process of movement of the future into the present and the present into the past. Optimism depends on the presence of ambiguity within the facticity of our situation. To be optimistic is to recognize that there is a seed of good here and now from which a person can, with sufficient will, build the future.

In Capitalist Realism Fisher proposes that this is the very thing neoliberalism sought to snuff out. We can see this desire, to bring about an end to history, in both the theoretical works of people like Fukuyama, who proposed history as an evolutionary process and the present moment as its final form (eliding both that human social development has never been evolutionary in character but rather more like an ecological process in a state of metastatic equilibrium and that evolution itself has no end) and in the practical efforts of Margaret Thatcher’s “no alternative” rhetoric, the neoliberal order is sustained in its own perilous equilibrium largely by the lie it foments that this is all we can strive for: a present that is always at the end of the arc of history curving inevitably toward freedom. A past that is always a time of darkness and superstition. A future that is more present but just with a faster phone with more pixels in the screen.

In such a future there is no place for the agency of revolutionary optimism. The neoliberal order hardly even likes to admit the agency of people is a good. Populism is made a dirty word and equated exclusively with fascists. Government becomes technocratic – governance a task best left to experts like some perverse materialization of Plato’s philosopher kings. But in a world where agency must always accompany professional expertise there is a place for hope. Perhaps, in the future, The Experts will make things better. A person who is an agent of hope thus ends up fighting a rear-guard action for the status quo. Any upset too far, any reactivation of history, carries with it the risk that the outside agents who hold aloft the light of hope cannot come and save us.

The neoliberal circumscription of the imagination has certainly had a negative impact on science fiction. In the precursor novel to cyberpunk, “The Sheep Look Up” the future was bleak. The novel traces the dissolution of the American empire after all and it does so with an unflinching eye to the circumstances of empire. However even there we get a sense that alternatives exist. The problem isn’t a purely Malthusian one but rather one that is specific to a mode of production in a specific place and time, “We can just about restore the balance of the ecology, the biosphere, and so on – in other words we can live within our means instead of an unrepayable overdraft, as we’ve been doing for the past half century – if we exterminate the two hundred million most extravagant and wasteful of our species,” in other words the alternative will arise out of the funeral pyre of empire. At the other end of the cyberpunk genre, William Gibson built the story of Virtual Light entirely out of the grounding of the future in a material present – a vast real-estate deal might reshape a city if only a person has the right eyes to see it.

Of course there’s a cynicism in cyberpunk. It is very much a genre of pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the spirit. The little people who populate cyberpunk novels – the thugs and grifters, the couriers and the hackers are not movers or shakers. And yet, despite being vastly, overwhelmingly, outpowered by the forces arrayed against them, they do their little hustles, carve out space for a future, for a history. This is because cyberpunk, charting that thread of science fiction between Brunner and Dick at one end and Gibson, Sterling and Stevenson at the other, was in many ways a punk genre.

Punk rock arose contiguously with cyberpunk. In retrospect 1968 had repercussions much farther afield than the French academy and this sense that the alternative future offered by the Soviet Union was perhaps as failed as the future offered by the United States informed many of these cynical quests to find an optimism of the will within pessimistic times. Within music this arose largely as a matter of distrust in the studio system and an unwillingness to participate in those syndical games compromising artistic vision. And so we have the Fugs announcing that they “dreamed of a bum, seven foot tall, who crushed the Bourgeoisie with a cross,” and we have Iggy Pop singing about his own desire for subjugation, “now I wanna be your dog.” The music, carving our an optimism of the will via a rejection of a formal system in favour of embracing the limits of do-it-yourself aesthetics contained within it the realization of a potential new future for music – a continuation of history by turning away from money and from polish in order to access something primordial: a broken and jagged scream that had no place in the institutions of the time.

Of course punk was recaptured by capital and the Stooges gave way to Blink 182. The bringing of punk to heel was a death by a thousand cuts. It may have begun with the style-before-substance empty anarchy of the Sex Pistols but there was no one moment before which punk was good and after which it was bad. Green Day were part of the punk-pop movement and yet they still carried with them that yearning for things to be different that characterized more radical precedents like the Dead Kennedys. Even now punk produces acts like Red Bait as well as acts like Paramore.

The capture of Punk was a suffocation under new axioms. Punk might be music for hoodlums and thugs but if it bends this direction or that, if it can become a vessel of a form of commodity fetishism, then places can be carved out for it. Crust punks might still gather in the living rooms of squats to reintroduce the primal scream of punk but they can be disregarded as long as carefully manicured ballads to teen angst played over three chords could also be allowed. Punk was expanded, not stylistically, there was always already a vast panoply of sounds to punk whether it’s the folk-sludge of the Fugs and the amateurish jangle of the Stooges or the surf-rock riffs of the Dead Kennedys and the Celtic lilt of The Real McKenzies – but rather it was expanded ideologically so that its initial rejection of the systems it was formed as an escape from became unnecessary – not incompatible, just unrequired. It’s important in this to keep in mind that what we see is a division of punk into these two components. The first is a punk aesthetic – a carrier of the artistic form associated with punk. The second is a system of material relationships with art. It describes a set of social and economic relations to art along with an underlying ethic regarding the purpose of art. This we could generalize as a punk ethos. This ethos does not need to map perfectly onto a specific aesthetic, which is why we could call acts that aren’t precisely within the punk genre of music (notably Gaylord and Feminazgul) as strong examples of the continuation of this ethos along with the aforementioned Red Bait.

A similar expansion was occurring in the waning days of cyberpunk. In 1990, William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, two of the luminaries of the subgenre, wrote The Difference Engine. This novel proposed an alternate history where Charles Babbage successfully created an analytical engine and where the British labour movement was subsequently crushed much sooner. This novel sought to trace a technological inevitability to neoliberalism and its anti-labour positions, as if the computer was responsible for crushing miner’s strikes. While I’m quite critical of The Difference Engine and its positioning of technology as the engine of history more than humans it was still effectively a cyberpunk work – its position in 1855 was to put forward the argument that the present age would inevitably arise when the technological conditions existed. The Difference Engine proposes the cyberpunk dystopia as the end of history.

However this novel also acted to pry open the definition of literary punk via the anointing of a successor in the form of Steampunk. Steampunk was a failed read of The Difference Engine that latched onto the aesthetic indicators of the second half of the nineteenth century as imagined by a deranged clock maker. Certainly Babbage’s computing engines were machines of gears and precision, but this is largely where the analysis of the Steampunks ended.

While Gibson and Sterling acted to critique the relationship between the industrial revolution and novel technologies by introducing a novel technology from the information revolution into the mix the Steampunk fandom were mostly just interested in the aesthetics this critique was clad in – the aesthetics of the Victorian world.

Steampunk provided an easy way to market all kinds of alternative histories diverging at some key technological nexus: Dieselpunk, Atompunk, Biopunk, and all the other -punk subgenres arose not directly from Cyberpunk but rather from the fannish under-interpretation of this one late-cyberpunk text and from the many imitators that tried to ride on the coattails of its success. If Steampunks had one last connection to anything punk it was via a DIY sensibility surrounding costuming that wasn’t honestly particularly unique within cosplay as an artistic movement. All cosplayers lionized the self-made costume over store-bought. Only Steampunks tried to say this made them punk.

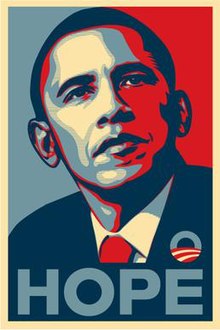

By the time Hopepunk was codified as an aesthetic positionality, punk had become nothing but a floating signifier – its boundaries had been so expanded that virtually any work of art could be called a punk text. This was the final defanging of punk as a genre. Red Bait and their radical ilk only manage to hold on by disregarding the punk label entirely and instead presenting a punk ethos. Hopepunk arose out of the bromine claim that “hope is punk” but it should be obvious by now that such a claim is farcical. Punks do for themselves, they make and they perform, they live in the margins and the recesses. Punks may have a pessimism of the intellect – a cynicism of the world as a broken place. But Punk, any remnant of the Punk ethos that remains in the wake of its defanging, insists on the agency of its participants. Punk doesn’t hope that the world will be better and instead gets on acting with autonomy in the world that is. Punk is materialist.

So, no, hope is not punk. It’s not punk at all. But this isn’t sufficient to render Hopepunk entirely occluded within its antimonies because, arising as it did from the fandom thread tracing back to Steampunk there’s no need for a punk ethos within Hopepunk for it to claim the -punk suffix. It’s just an intrinsically meaningless sound used to denote the aesthetic center of the subgenre. A -punk suffix does nothing but direct the reader that the prefix carries the essence of the subgenre. Dieselpunk is about trains. Atompunk is retrofuturistic nostalgia for the 1950s. Steampunk is the second half of the nineteenth century imagined as if their technology exceeded our own while retaining the aesthetic character of the industrial revolution. Hopepunk is likewise uninterested in being punk in the sense that The Stooges or The Sheep Look Up is punk but is instead interested in centralizing the experience of hope as its central aesthetic concern.

Thus far we cannot say much about Hopepunk. It certainly isn’t punk but we can hardly fault it for that. It is simply using common understandings to communicate that the emotion of hope is the essence of the genre. But, as I said, hope is something of a slippery emotion – it is an essentializing of optimism that divorces it from a material basis via an absolute rejection of facticity. But all this says is that Hopepunk is an idealist literature. However Hopepunk does not lack for manifestos.

Perhaps the most important of these would be an untitled essay of Alexandra Rowland’s from 2017 where she expands upon the statement that Hopepunk is best understood as the opposite to Grimdark saying that the older subgenre’s essence, “is that everyone’s inherently sort of a bad person and does bad things, and that’s awful and disheartening and cynical. It’s looking at human nature and going, “The glass is half empty.”

No examples are provided of what Rowland considers to constitute a Grimdark literature. We could surmise she might be referring to the work of fantasists such as Joe Abercrombie who take a more discursive tone to the fantastical, interrogating the essentialism of good and evil presented in classics such as the Lord of the Rings. Rowland includes this text as a Hopepunk text, along with The Handmaid’s Tale, “Jesus and Gandhi and Martin Luther King and Robin Hood and John Lennon,” to put forward something of a Hopepunk canon.

Now there are a few things we can take from this essay of Rowland’s regarding her characterization of Hopepunk. We can see it as existing in a broadly liberal space. There’s a certain lack of criticality to including John Lennon alongside the mythical founder of one of the world’s largest religions. Rowland gestures toward people who are, however, enmeshed in a specific kind of liberal sense of the Good. John Lennon earns his spot next to Jesus not because of any sort of shared facticity but rather by the shared beauty of their imaginations. She’s treating these disparate figures as their texts, comparing The Sermon on the Mount to King’s Dream speech to Lennon’s Imagine. Alongside this treatment of these people as text she’s using the object of their deaths to create her essence, interrelating the martyrdom of Jesus King, Ghandhi and Lennon too. Tolkien is Hopepunk too – after all there has rarely been a greater master of the idealist fantasy than he – but this is with a slight caveat that situates the example as a specific interpretation of the text by Sean Astin in a specific scene of The Two Towers film.

What can be drawn from Rowland’s examples is that she is pursuing an idealist Good as an objective of fiction. She gestures that people may not succeed all the time – most people aren’t John Lennon after all – and much of her political language is very much of its time and place as an American Democrat in the early days of the Trump presidency. However we can certainly situate Hopepunk as a liberal literature that is quite welcoming of conservativism as long as it is the friendly idealist version put forward by old JRR.

Rowland wrote a second manifesto in 2019 which I think serves as a clarification of the 2017 definition. In this she posits that the crux of her argument is that, “being kind is a political act. An act of rebellion.” I think she does something interesting here in situating a positionality for the ethic of Hopepunk in a specific class when she says, “But once in a while, the people toward the middle of the heap manage to look down and see the mass of wretched bodies below, the base of the pyramid that’s supporting them, and for a moment, they see the instability of their own position, that their pyramid isn’t built on solid ground but on human flesh and human pain.” Of course, the, “middle class,” is no class at all. As Deleuze and Guattari put it, under late capitalism, “there is only one class, the Bourgeoisie.” Absent this striation you get nothing but this undifferentiated pyramid of suffering. “The middle of the heap,” is a dangerously reductive statement compared to the clarity of a working class. And I do want to make sure that it is entirely clear from the context of this essay that “the middle of the heap,” can be taken to mean, “us.”

Rowland seems to have pivoted from a clear liberal idealism in 2017 to a position more akin to a humanist existentialism in 2019. This humanism is largely being brought in by way of the great humanist satirist Terry Pratchett. However much of her attempt at devising an aesthetic seems to largely be a frame for her personal response to the declining political situation of the United States across those last pre-COVID years. Rowland says, at one point, “The world has always and only been a never-ending, Darwinian struggle for survival, an ’empire of unsheathed knives and hungers,’ clawing at each other and climbing over each other in a mad riot, pushing our boots down into someone else’s face to heave ourselves up a little higher or risk being trampled ourselves.” This, together with the bleak picture of the middle of the heap complexify her humanism in uncomfortable ways. It’s hard to see both the kind of Beauvoirian ethic she attempts to approach in this article when you are also seeing all of human culture as a demonic crab bucket.

When Rowland returns to Hopepunk after this rather bleak precis she starts by claiming, “First, you must understand that everything is stories: money, manners, civilization. It’s all just little tales we tell each other, little collective hallucinations. A set of rules so that we can all play pretend together.” This fixation on culture as text is very nearly Derridean in its focus but misses the mark a bit when it reduces the concept of narrative, of text, to “little collective hallucinations.” This becomes a return to a kind of idealism, a sense that there is no world beyond the mind and that noumen are inaccessible to us. Rowland’s critique of the decline of the American empire under Trump stumbles over this refusal of materialism. She lacks anything like an optimism of the spirit in this moment of this text. And as I said before, hope is a dialectical unity with despair.

Rowland tries to bridge this despair with a valorization of stubbornness. Again the problem remains this focus on an idealist worldview wherein the social field is just a network of hallucinations or, as she quotes Pratchett, little lies. But then she does an odd pivot in an attempt to create a companion subgenre to Hopepunk in “Noblebright” (another attempt at an opposite to the still-undefined Grimdark).

“Noblebright is about goodness and truth and vanquishing evil forever, about a core of goodness in humanity. It’s most of the Arthurian legends, the Star Wars original trilogy, Narnia . . . in Tolkien terms, it’s Aragorn, rather than Frodo and Sam (who are hopepunk as hell). In noblebright, when we overthrow the dark lord, the world is saved and our work is done. Equilibrium and serenity return to the land. Our king is kind and good and pure of heart; that’s why he’s the king.

It’s all very nice,” she says. And Rowland, during the more desperate period of her essay in which she reflected upon the politics of the moment has been quite critical of niceness. Rowland tries to create a discourse between this proposed subgenre and Hopepunk, using them to tease out the aforementioned Beauvoirian ethic except that her idealist approach serves her poorly there. “It’s about being kind merely for the sake of kindness, and because you have the means to be, and giving a fuck because the world is (somehow, mysteriously, against all evidence) worth it and we don’t have anywhere else to go anyway.” Somehow, mysteriously, against all evidence. This, then is the return to hope contra optimism I mentioned before. Rowland doesn’t want to look for the Good in her facticity but rather to find it against all evidence.

In the end Rowland turned from a pure sort of Liberal idealism in 2017 to a kind of existentialism in 2019 – but in doing so she occluded an actual definition of Hopepunk even further. What is Hopepunk? It’s an idealist literature of a non-existent class that attempts to respond to power with aphorisms about the value of kindness but an avowed willingness to lean into ambiguity. This makes it even harder to square some of the many disparate examples. Aside from one song how does any of this apply to the man who sang Taxman – a protest song against progressive taxation under a Labour government? How could this attempt at a radical idealist kindness lionize a political leader who was all too happy to call Hitler his “dear friend,” a man who was all too happy to deploy racist arguments about Black South Africans if it meant improving the position of Indians within the colony? In Rowland’s two manifestos much changes. Her entire ideological frame seems to shift and she attempts to pivot Hopepunk with it. It isn’t enough to have constructed a strawman in “grimdark” against which to measure this vague subgenre but now a second one, “noblebright,” must be deployed as a foil. And of course the examples for “noblebright” fiction are safely anachronistic. Star Wars may, in fact, be the most recent work of art mentioned and I would propose that Rowland may have misapplied her rubric. If she believed truly that, especially that first film dealt in absolutes then she might want to consider revisiting the text of Star Wars from the perspective that the Jedi aren’t entirely reliable expositors. Ultimately an attempt to sketch what Hopepunk actually is will need to leave Rowland behind. She’s critical to its formulation but her manifestos are impacted to their detriment by her obvious attempts to process the failure of American liberalism without letting go of American liberalism entirely. We must expand our field of view.

The Jesuit priest Jim McDermott contributed an interesting thread to the definition of Hopepunk by claiming it for Catholicism largely through the invocations of Tolkien and Lewis in its formation. Writing in 2019 he elaborated on Rowland’s essay first by attempting to define “grimdark,” describing its central texts as, ““The Walking Dead,” “Breaking Bad” or the Zack Snyder-helmed DC Comic book movies.” On the other hand, McDermott sees a reflection of his faith in Hopepunk, saying, ” hopepunk insists there are streams of life-giving water all around us—stories, people and experiences to which we can still turn for inspiration and renewal. Our very faith is built upon such a story, one in fact so ridiculously unafraid of the worst that reality can throw at us that it chose to make the moment of its most horrendous loss the icon of its hope.”

For him, the thread of the valorization of the martyr found in Rowland’s first essay is key and he repeats her invocation not just of Jesus but of Martin Luther King Jr. This inclusion is interesting since his thesis is so specifically to claim Hopepunk for Catholicism and King was a Baptist. But he is writing for an American catholic publication and King is not just a Christian martyr but also a principal martyr of the American civic cult so I suppose this fits the specific syncretism of the American Liberal Priest just fine. McDermott is a poetic essayist, it’s sure and his conclusion is beautifully worded, “That is the point and opportunity of hopepunk: the Spirit does not follow the rules we set down. Grace rebels and God thrives not in some impossible sanctity but in the actual mess of our humanity.” But this merely reinforces the idealist thread of Rowland’s work. His reading of Rowland is one of a transcendental soul upon which a moral field acts. The other commonality between McDermott and Rowland’s definitions of Hopepunk is that both assume a clear ethical dimension to art – for both authors art exists to communicate Good whether that’s Rowland’s vaguely secular humanistic Good or his more explicitly Catholic ethic.

Aja Romano also situates Hopepunk as beginning from Rowland’s pronouncement in opposition to “grimdark” however she treats it more as a literary movement than an aesthetic or an ethos. Romano implores her audience to “picture that swath of comfy ideas” and I think this is a very important dictum as the Hopepunk ethic is very much rooted in the literary concept of the cozy. It’s a fiction that tries to keep the mean stuff off the page as much as possible. We know orcs are bad and Sauron worse but we don’t see the torture chambers of Mordor – we just hear about them. Cozy novels want to encourage an integrated audience who can ride along with the characters of the story in maximum comfort. This is largely a utilitarian motivation as in the mystery genre, where the cozy is particularly prevalent, this comfort with our characters allows the audience to solve the crime along with the detective. The Cozy arises in other context too though, with On The Beach being a key early example of the cozy apocalypse. Out there everything has fallen apart but over here things still go on in a way as we all await the end quietly, contemplatively, inevitably.

Romano shares the same examples of “grimdark” as McDermott albeit with a bit more shade for Nolan and a bit less for Snyder and here is where we begin to see part of the problem with Hopepunk’s search for a moral essence in fiction because they fail to differentiate Breaking Bad as a text from the worst audience responses to the same. Breaking Bad is flatly satirical – a vicious attack on the American healthcare system, the American education system and a case study in how one vicious little man can befoul the lives of the people around him all while pursuing a perverted idea of the American Dream. Though weakened by the dramatic positioning of the “One who knocks” speech and Bryan Cranston’s career-defining performance there was nothing in Breaking Bad that suggested that Walter White should be anything other than a moral warning. There is an ethic underlying Breaking Bad and it is one that is fundamentally critical of our Heisenberg. The finale of Season 2, in particular, should dispel any notion that Walt is anything other than a moral hazard for everyone around him. The way it builds so much death and pain off of chance encounters doesn’t lionize his bad behaviour – it condemns it. But this seems missed by a literature that desires a moral lesson in a cozy package.

Romano also draws out in text some of the subtext in Rowland’s first manifesto, describing Rowland’s strange Jesus and John Lennon list as, “heroes who chose to perform radical resistance in unjust political climates, and to imagine better worlds.” I believe I’ve dwelled enough on the heroism of Ghandi and John Lennon’s heroism for one essay but suffice it to say I am uncomfortable with calling either of them, especially, heroic.

Romano is honest about the frustrating vagueness of definition in Rowland’s manifesto saying, “The broad strokes of Rowland’s definition mean that a lot of things can feel hopepunk, just as long as they contain a character who’s resisting something,” but she attempts to supersede Rowland’s insufficient definitions, providing a bulleted list of aesthetic parameters including, “A weaponized aesthetic of softness, wholesomeness, or cuteness — and perhaps, more generally, a mood of consciously chosen gentleness,” and, “An emphasis on community-building through cooperation rather than conflict.” I think this essay is the first time we get a clear sense of the problem presented by Hopepunk as a narrative construction: Romano refers to it as being of a cloth with, “an extreme, even aggressive form of self-care and wellness” and this, combined with its idealist connection to an ethic and its discomfort with critical depictions of cruelty leave Hopepunk a relatively empty form made principally out of blind spots.

We’ve seen what aggressive self-care often looks like and that is an expulsion of discomfort. An oyster who encounters a piece of grit responds by forming a pearl around it but this aggressive advocacy for cozy fiction mostly ends up being much more like a Sea Cucumber expelling its own innards to escape a threat. Romano describes Hopepunk as possessing the aesthetics of Bag End – being fixed upon comfort and she attempts to equate this comfort-seeking with some sort of radical rejection of work. This seems otherwise unsupported by the available texts. Certainly it’s at odds with Rowland’s vision of Hopepunk as a proactive tool of protest.

Romano also expounds on the link between Harry Potter and the September 11 attacks of 2001 (not to be confused with the far-more tragic September 11 of 1973) suggesting that the, “films provided essential tales of optimism in response to widespread narratives of war and anti-globalization.” Anti-globalization is an interesting insertion into this discourse considering how activities such as the Alter-Globalization movement were recharacterized, following September 11, as anti-globalist, and the demands that neoliberal exploitation of multilateral trade be restricted were reframed as some sort of impossible demand to return to a protectionist past. Of course plenty of ink has been spilled about the neoliberalism of Harry Potter. After dwelling on various strands of Potter-branded activism Romano turns to the claiming of additional fictions that are built around emotional empathy as Hopepunk, fixing her attention on Sense8 in a move that I think grossly misses the point of that show.

“Even more, in the literary sense, hopepunk has the power to embed the conscious kindness that Sam encourages within the worldview and worldbuilding of a story itself.” Romano says and this reinforces the sense that Hopepunk, as a literary movement, has specific expectations not only of the message of a text but also its form. It’s not enough that evil be repudiated by the authorial voice, comfort must be baked into the very worldbuilding of the story. It’s unsurprising that the luminary texts of Hopepunk are principally mass-market fantasies.

Romano is also one of the first voices within this literary movement to articulate an actual target within “grimdark” literature, via Game of Thrones though even here it’s cloaked through reference to a filmic adaptation as she interprets Jon Snow as “a chosen one,” figure, seemingly oblivious to the fact that Martin’s Work in a Song of Ice and Fire was explicitly problematizing the idea of the “chosen one trope” and was critical of it.

This is where the idealism of Hopepunk makes it ultimately unsuited to a revolutionary task. Hopepunk is incapable of recognizing a critical movement within literature. So fixed on surfaces, on televisual and filmic representations of kindness and empathy, that it fails to see that Walter White is the bad guy of Breaking Bad or that Jon Snow remains, to this day, dead in the snow and betrayed by his brothers in the books. Hopepunk, when deployed as a critical standpoint, has terrible aim. Its central formulators want to claim it as a weapon against oppression and the far-right but will only countenance this rebellion if it is comfortable. Absent this demand of comfort Hopepunk becomes so nebulous that about all you can say of it is that it is a vaguely Bourgeois fiction that traffics in idealistic understandings of the Good, which is to say it’s just fantasy fiction. Standard fantasy fiction.

Hopepunk loves a martyr and McDermott is quite right to call it a Christian fiction, even if he reaches too far in claiming it for Catholicism in particular. The true believers of the movement see it, quoting a friend of Romano, as “some seriously important and sacred shit!” But Hopepunk struggles as a fiction of the sacred because it also wants so badly to be a humanist fiction. It’s frustrating to see people approaching Pratchett in the same breath as Tolkien considering how much the former’s career served as a critique of the latter. But again this points back to the fixation of Hopepunk with comfortable surfaces. It’s easy to look at Death in Hogfather talking about little lies and to stop there. But to avoid that you’d need to be blind to the historical materialism of the Hogfather’s growth from a seasonal sacrificial rite to a commercial holiday. Pratchett is deeply and critically involved with the enmeshment of the social field in the material. The point, the real point, of Hogfather is that they aren’t lies at all. That place where the rising ape meets the falling angel is materiality, it’s a human condition that exists within history, within matter. This is why the Auditors cannot win. They don’t understand the materiality of culture – they mistakenly assume the material is just rocks moving in arcs.

I think Rowland’s 2019 essay is perhaps the best possible version of a Hopepunk we could expect until it divorces itself from the liberal legacy of the fantasy mainstream. Her attempt at an existentialist ethic misses key qualities of Beauvoir’s materialism in The Ethics of Ambiguity but she does grasp well the idea of the pursuit of the good as a task without an end, a task that exists in a state of ambiguity. However I think the version of Hopepunk that actually exists is the far more frustrating version put forward by Romano. This is the version that is obsessed with an aesthetic of comfort, that refuses to engage with anything critical because it might seem unkind. Romano’s framing of Hopepunk will never produce pearls although it has a legacy of driving two years of twitter feuds.

I do think a revolutionary literature is valuable but for a literature to be revolutionary it must have three qualities Hopepunk lacks: a critical response to extant material conditions, a willingness to explore discomfort and a complete rejection of the status quo. A revolutionary literature doesn’t require hope – but it does require pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will. Frankly, a revolutionary literature has to, in the end, be truly punk.

Pingback: Notes on Squeecore | Simon McNeil

Pingback: 👏 This 👏 Is 👏 So 👏 Important 👏 | Towards a New Dark

Pingback: The First Time as Tragedy, the Second Time As Farce: The dialog of Bodies Bodies Bodies and Glass Onion | Simon McNeil